The history of Aladdin

Aladdin is one of the most iconic tales from The Thousand and One Nights (or The Arabian Nights), but its origins are more complex than many realise. Interestingly, the tale did not appear in the original Arabic manuscripts but was introduced by French scholar Antoine Galland in the early 18th century. Galland heard the story from Hanna Diyab, a Syrian traveller and storyteller, whose retelling became part of the Western version of The Arabian Nights.

The Thousand and One Nights is a collection of Middle Eastern folktales compiled during the Islamic Golden Age, believed to have originated in the 9th century. The stories within the collection were passed down orally across different cultures, including Persian, Indian and Arabic influences. The overarching tale is about Scheherazade, a young woman who tells a new story every night to her husband, King Shahryar, to avoid execution. Each night, Scheherazade weaves tales filled with adventure, magic and moral lessons, creating a rich tapestry of storytelling.

First published in 1704, Galland’s The Thousand and One Nights, which he translated from a fifteenth-century Arabic manuscript, was a smash-hit and there are reports that Galland was often woken up by visitors haranguing him from the street below, imploring him to release more stories.

By 1709, however, Galland had run out of stories to translate from available manuscripts, and his publisher was padding out the latest volume with stories by other writers. But the luck so often found in fairy-tales was with Galland and a colleague in Paris introduced him to Hanna Diyab, a young man who told him the Story of the Lamp and fifteen other stories over a series of meetings.

Although Aladdin was not part of the original manuscript, it is easy to see why this magical adventure found a home there, and the story has become synonymous with The Thousand and One Nights in Western culture, thanks to its inclusion by Galland. Other famous tales from the collection include Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves and The Seven Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor.

Aladdin through the years

In its earliest form, Aladdin is set in China, but the story’s elements are largely Middle Eastern. Aladdin is a poor, lazy boy living with his widowed mother when a sorcerer from North Africa, who claims to be the lad’s uncle, tricks him into retrieving a magical lamp from a booby-trapped cave. This lamp contains a powerful genie, whose magic grants Aladdin immense wealth and power. With the genie’s help, Aladdin rescues and marries Princess Badroulbadour and outwits the sorcerer.

Along the way, we meet the Genie of the Ring and a magical Flying Carpet, although the latter was most likely added by Galland.

But is any of it true?

While Aladdin is primarily a folktale, some scholars speculate that elements of the story may have been inspired by Hanna Diyab’s life, as there are parallels between the protagonist’s journey and Diyab’s personal experiences.

In 1993, a previously unknown autobiography-meets-travelogue by Hanna Diyab was uncovered in the Vatican Library. Written in 1763, the memoir recounts vivid tales real-life tales of adventure that include wonders, bandits, and betrayal. Diyab also discusses his former ’employer’ Paul Lucas, who is painted as a untrustworthy wrong ‘un. Of particular note is the episode in which Diyab describes how Lucas, ever in search of archaeological treasures, took an interest in exploring the ruins of a church in a Syrian village near Idlib. He persuaded a local shepherd boy to venture into a vault beneath a rock, from which the boy emerged clutching an ancient ring and a lamp. Could this have sown the seeds for the story of Aladdin? Or did Diyab add these elements to a story rooted in folklore?

While there’s no clear historical figure associated with Aladdin, the tale continues to resonate with audiences because of its universal themes of adventure, transformation and the power of wit and determination. Plus, who doesn’t love a genie?!

You ain't never had a friend like Disney

The 1992 Disney animated film Aladdin gave the story new life, setting it in a fictional Middle Eastern city called Agrabah and introducing characters like Jasmine (who replaced Badroulbadour) and the villainous vizier Jafar (who takes the ‘baddie’ role in place of the evil magician/fake uncle). This version brought the story to a global audience, thanks in part to the iconic portrayal of the Genie by Robin Williams, its vibrant animation and its catchy songs.

A major hit, Disney’s Aladdin was the highest-grossing film of 1992, earning over a whopping $346 million in worldwide box office revenue. The film was followed by a live-action adaptation in 2019, which surpassed the original film within a month of its release, earning $604.9 million worldwide and further cementing Aladdin as a beloved story in popular culture.

More on the Silver Screen

The tale of Aladdin has been a rich source of inspiration for filmmakers, leading to a variety of adaptations that reflect the evolving landscape of cinema.

One of the earliest cinematic interpretations is Aladdin and the Wonderful Lamp (1917), a silent fantasy film that brought the enchanting story to the silver screen during the silent film era. This adaptation set the stage for future retellings of the classic tale.

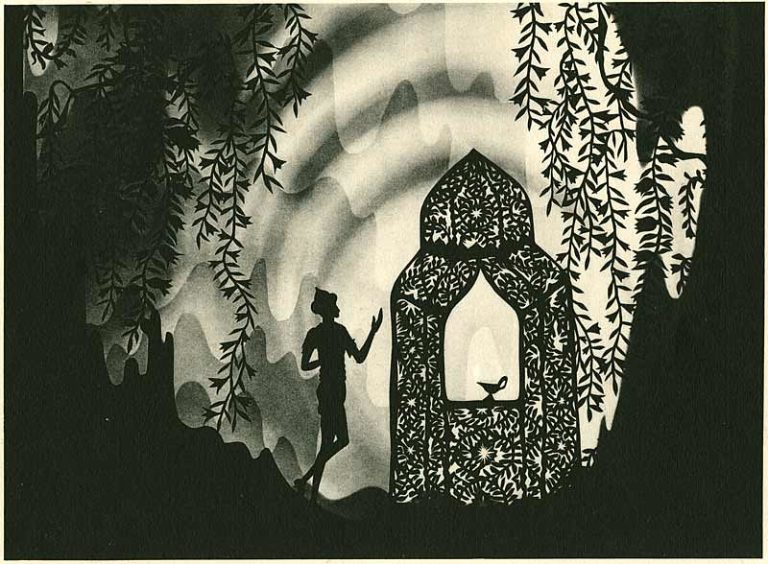

In 1926, German filmmaker Lotte Reiniger released The Adventures of Prince Achmed, recognised as the oldest surviving animated feature film. This pioneering work used silhouette animation to weave together elements from One Thousand and One Nights, including the story of Aladdin, showcasing the narrative’s versatility and appeal across different cultures.

Disney’s early exploration of Middle Eastern themes is evident in the 1932 animated short Mickey in Arabia, in which our hero, Mickey Mouse, embarks on an adventure set against an Arabian backdrop. This short reflects the era’s fascination with exotic locales, albeit through a Western lens.

The 1940 fantasy adventure The Thief of Bagdad shares several motifs with the Aladdin story, featuring a princess, a flying carpet and an evil vizier named Jaffar. This film exemplifies Hollywood’s penchant for exoticism, often prioritising spectacle over cultural authenticity.

In 1952, Aladdin and His Lamp was released, notable for its toe-curlingly awful tagline: “See the world’s most gorgeous harem beauties.” [See earlier note on Hollywood’s tendency to exoticize and sensationalize Middle Eastern culture.]

On with the show...

In the UK, Aladdin is one of the most beloved pantomimes, a staple of British theatre that embodies the genre’s signature mix of humour, slapstick and audience participation. Like all pantos, Aladdin delivers a joyful blend of family-friendly entertainment and cheeky, often topical comedy. The pantomime version of Aladdin typically features a host of colourful characters, including Widow Twankey, Aladdin’s hilariously over-the-top mother and the traditional pantomime dame, Wishee-Washee, his loveable but dim-witted brother, and Abanazar (Boo! Hiss!), the scheming magician bent on acquiring the magic lamp for his own nefarious ends. The genie, whether played by an actor or represented through special effects and a booming voice, adds a sense of wonder and magic that captivates audiences of all ages.

Over the years, Aladdin has become one of the most lavishly staged pantomimes, celebrated for its vibrant costumes and elaborate sets. Its setting, often a mythical version of China, reflects a Victorian fascination with the Far East, which audiences of the time found exotic and intriguing. The first performance of Aladdin as a pantomime dates back to 1788 at the Theatre Royal, Covent Garden, but the modern version owes much to Henry J Byron’s 1861 burlesque Aladdin, or the Wonderful Scamp. This production popularised the chinoiserie-inspired costumes and sets that became a hallmark of the show, complete with pagodas, ornate props and Widow Twankey – named after a Chinese green tea – often portrayed as running a Chinese laundry. With its lighthearted take on the classic tale, Aladdin remains a festive favorite, having been performed by stars such as Norman Wisdom, Cliff Richard, Cilla Black, Shane Richie and Alesha Dixon, who have each brought their unique sparkle to the title role.

Why is Aladdin such a popular story?

The enduring appeal of Aladdin lies in its timeless themes of adventure, transformation and triumph over adversity. At its heart is a classic “rags to riches” tale, but one wrapped up in the story of an active, plucky and mischievous hero – a loveable scamp who prevails through cleverness, courage and a generous dose of good luck. Add in some magical elements such as a genie, a magic lamp and a flying carpet, and you’re on to a winner.

Aladdin‘s central message of overcoming obstacles speaks to universal human experiences, and our hero’s journey from humble, impoverished laundry lad to a celebrated hero continues to captivate audiences with its blend of ambition, love and self-discovery.

The story’s versatility means it works as a fairy-tale, animated smash hit or hilarious pantomime. Endlessly adaptable, each retelling of Aladdin brings a fresh perspective, whether its slapstick, romance or adventure. This ability to evolve, coupled with its enduring themes, ensures Aladdin continues to transcend cultural boundaries and capture imaginations worldwide.

So make time for this beloved narrative this Christmas and enjoy the magical charm and relatable underdog journey that have cemented Aladdin‘s status as a cornerstone of storytelling. We are bringing this timeless tale to life on The Elgiva stage in our fabulous family pantomime and can’t wait for you to join us. Packed with songs, gags, magic, mischief and mayhem, Aladdin is a real Christmas cracker!